Merz’s vision is one of total mobilisation — a “whole-of-society” approach that seeks to prepare not just the armed forces, but the entire German economy and civil infrastructure for confrontation with Russia. Media, education, industrial policy and civil defence are all being aligned to support this new war footing. Dissent — whether political, journalistic, or academic — is increasingly stigmatised as subversive or even a threat to national security.

Ω Ω Ω

What we are witnessing is not a return of German nationalism, but its opposite. The policies now being implemented — from massive rearmament to the escalation of conflict with Russia — are not rooted in a cold pursuit of German national interests, but in their negation. They are the expression of a political class that has internalised the Atlantic ideology so thoroughly that it can no longer distinguish between national strategy and transatlantic loyalty.

Ω Ω Ω

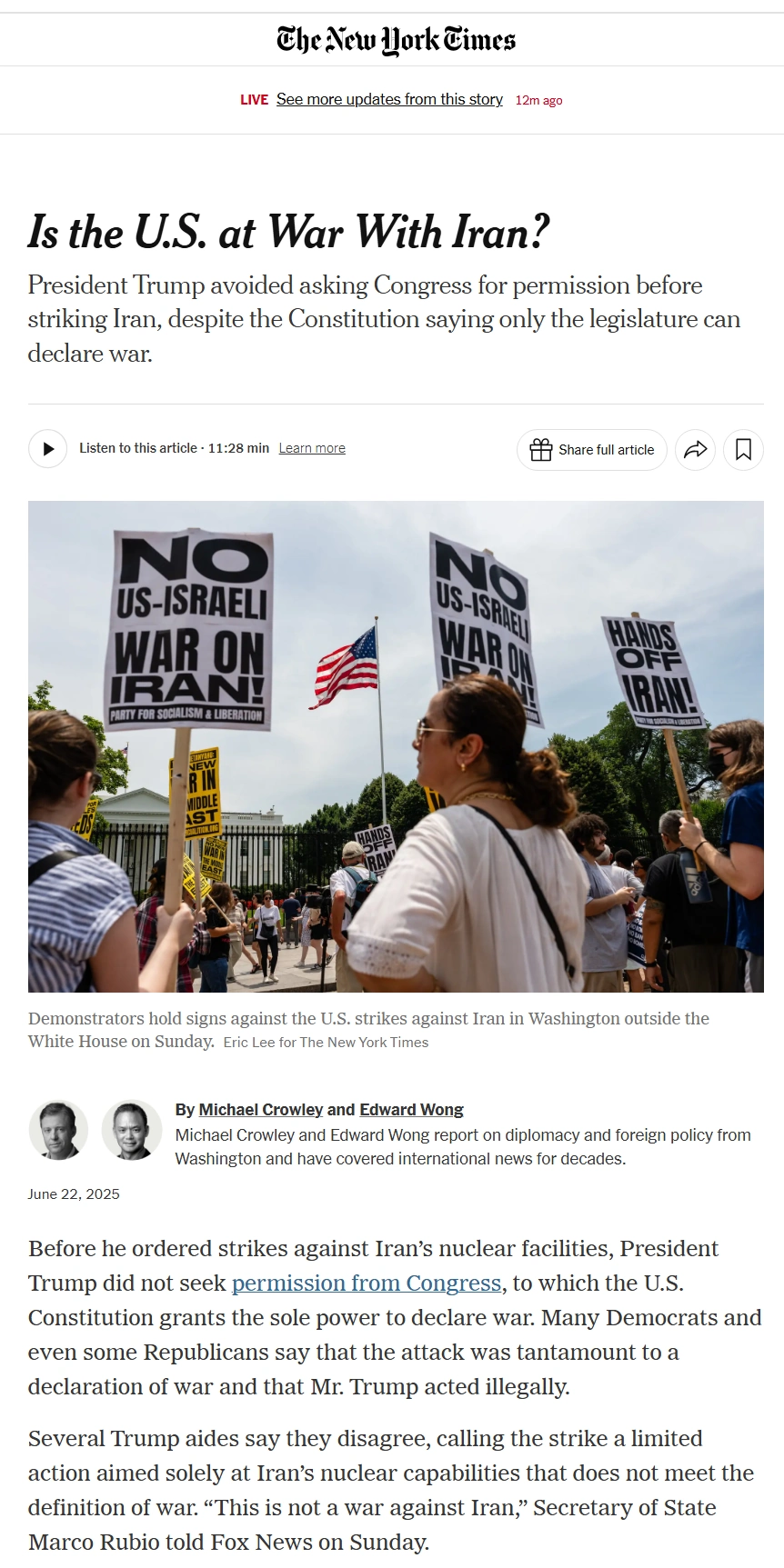

Merz, while publicly critical of Trump, is in fact executing Trump’s vision: pressuring Germany to drastically increase defence spending, take over leadership in the Ukraine war and sever energy ties with Russia. And yet they are presented as expressions of German and European sovereignty. Contrary to Schröder’s courageous stance against the US invasion of Iraq 20 years ago, Merz has also offered a full-throated endorsement of Trump’s recent attack on Iran.

The problem today then, is not German ambition, but German submission. And the tragedy is that this submission is being dressed up as strategic autonomy — a grim parody of sovereignty in an age of ideological dependency. If German leaders once understood that peace with Russia was in Germany’s fundamental interest, today’s leaders act as if permanent conflict is a condition of responsible statecraft. That reversal is not only dangerous for Germany, but for Europe as a whole.

-

Neueste Beiträge

Archive

- Juli 2025

- Juni 2025

- Mai 2025

- April 2025

- März 2025

- Februar 2025

- Januar 2025

- Dezember 2024

- November 2024

- Oktober 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- Juli 2024

- Juni 2024

- Mai 2024

- April 2024

- März 2024

- Februar 2024

- Januar 2024

- Dezember 2023

- November 2023

- Oktober 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- Juli 2023

- Juni 2023

- Mai 2023

- April 2023

- März 2023

- Februar 2023

- Januar 2023

- Dezember 2022

- November 2022

- Oktober 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- Juli 2022

- Juni 2022

- Mai 2022

- April 2022

- März 2022

- Februar 2022

- Januar 2022

- Dezember 2021

- November 2021

- Oktober 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- Juli 2021

- Juni 2021

- Mai 2021

- April 2021

- März 2021

- Februar 2021

- Januar 2021

- Dezember 2020

- November 2020

- Oktober 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- Juli 2020

- Juni 2020

- Mai 2020

- April 2020

- März 2020

- Februar 2020

- Januar 2020

- Dezember 2019

- November 2019

- Oktober 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- Juli 2019

- Juni 2019

- Mai 2019

- April 2019

- März 2019

- Februar 2019

- Januar 2019

- Dezember 2018

- November 2018

- Oktober 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- Juli 2018

- Juni 2018

- Mai 2018

- April 2018

- März 2018

- Februar 2018

- Januar 2018

- Dezember 2017

- November 2017

- Oktober 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- Juni 2017

- Mai 2017

- April 2017

- März 2017

- Februar 2017

- Januar 2017

- Dezember 2016

- November 2016

- Oktober 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- Juli 2016

- Juni 2016

- Mai 2016

- April 2016

- März 2016

- Februar 2016

- Januar 2016

- Dezember 2015

- November 2015

- Oktober 2015

- August 2015

- Juli 2015

- Juni 2015

- April 2015

- Januar 2015

- Dezember 2014

- November 2014

- Oktober 2014

- September 2014

- Juli 2014

- Juni 2014

- Mai 2014

- April 2014