-

Neueste Beiträge

Archive

- Juli 2025

- Juni 2025

- Mai 2025

- April 2025

- März 2025

- Februar 2025

- Januar 2025

- Dezember 2024

- November 2024

- Oktober 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- Juli 2024

- Juni 2024

- Mai 2024

- April 2024

- März 2024

- Februar 2024

- Januar 2024

- Dezember 2023

- November 2023

- Oktober 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- Juli 2023

- Juni 2023

- Mai 2023

- April 2023

- März 2023

- Februar 2023

- Januar 2023

- Dezember 2022

- November 2022

- Oktober 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- Juli 2022

- Juni 2022

- Mai 2022

- April 2022

- März 2022

- Februar 2022

- Januar 2022

- Dezember 2021

- November 2021

- Oktober 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- Juli 2021

- Juni 2021

- Mai 2021

- April 2021

- März 2021

- Februar 2021

- Januar 2021

- Dezember 2020

- November 2020

- Oktober 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- Juli 2020

- Juni 2020

- Mai 2020

- April 2020

- März 2020

- Februar 2020

- Januar 2020

- Dezember 2019

- November 2019

- Oktober 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- Juli 2019

- Juni 2019

- Mai 2019

- April 2019

- März 2019

- Februar 2019

- Januar 2019

- Dezember 2018

- November 2018

- Oktober 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- Juli 2018

- Juni 2018

- Mai 2018

- April 2018

- März 2018

- Februar 2018

- Januar 2018

- Dezember 2017

- November 2017

- Oktober 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- Juni 2017

- Mai 2017

- April 2017

- März 2017

- Februar 2017

- Januar 2017

- Dezember 2016

- November 2016

- Oktober 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- Juli 2016

- Juni 2016

- Mai 2016

- April 2016

- März 2016

- Februar 2016

- Januar 2016

- Dezember 2015

- November 2015

- Oktober 2015

- August 2015

- Juli 2015

- Juni 2015

- April 2015

- Januar 2015

- Dezember 2014

- November 2014

- Oktober 2014

- September 2014

- Juli 2014

- Juni 2014

- Mai 2014

- April 2014

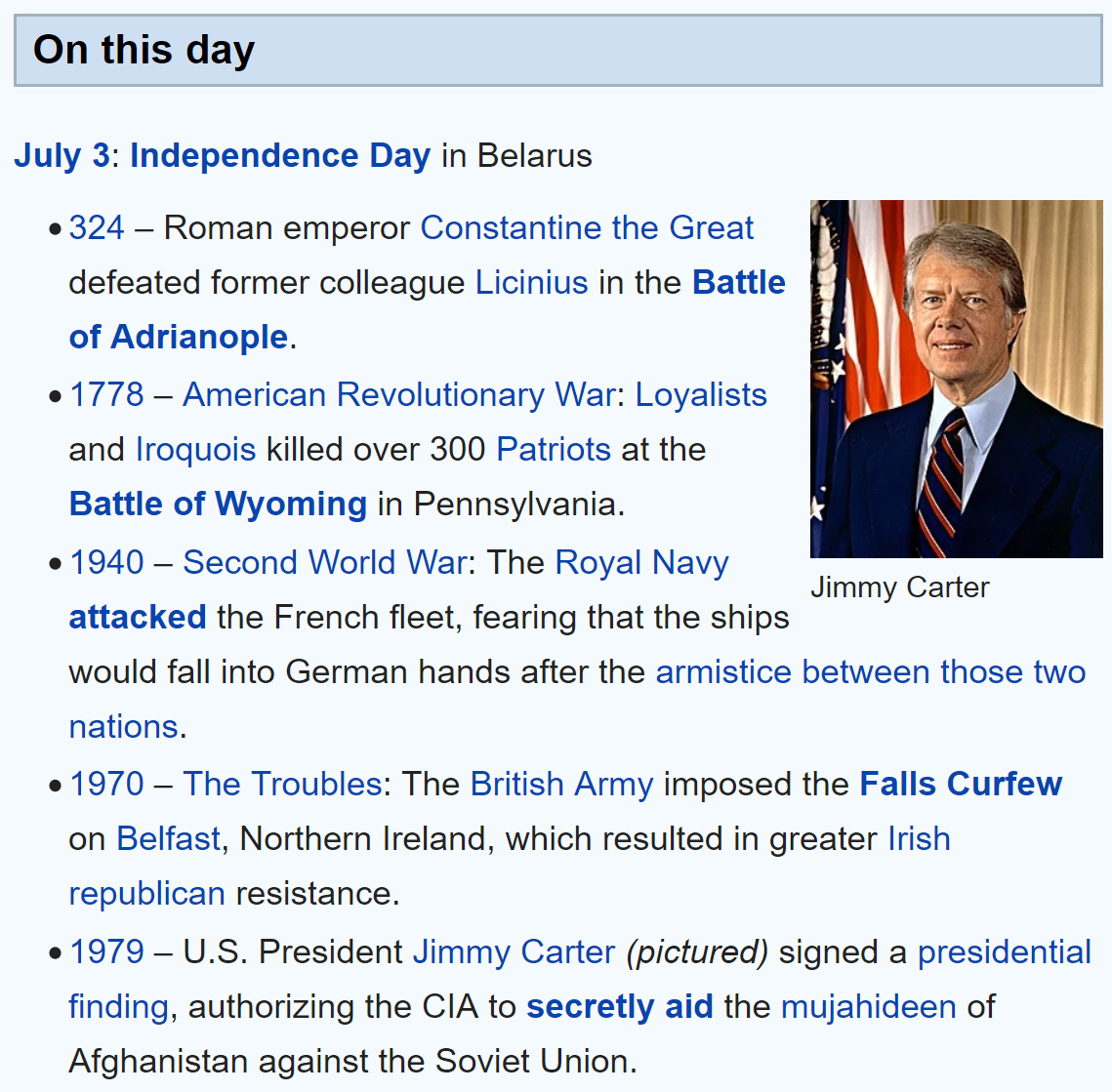

July 3, 1988

Iran Air Flight 655 was a scheduled passenger flight from Tehran to Dubai via Bandar Abbas, that was shot down on 3 July 1988 by an SM-2MR surface-to-air missile fired from USS Vincennes, a guided missile cruiser of the United States Navy. The aircraft, an Airbus A300, was destroyed and all 290 people on board, including 66 children, were killed.[1]

In between July 3, 1979 and July 3, 1988 we had another year and a half of Carter and then seven and a half of Reagan.

How the West Pushed Russia Into China’s Arms

Russia’s relations with Western Europe now lie in rubble; ending over three decades of attempts to build “a common European home.” That leaves a proud, wounded power available at a discount, ripe for Chinese influence in ways the Kremlin itself once worked hard to avoid.

What Nechapurenko shows — with all the vivid detail of red lanterns, panda statues, and Mandarin catchphrases on Moscow’s metro — is the cultural dimension of that pivot. And culture matters. It is the deeper loom on which long alliances are woven. If young Russians grow up seeing China not as the Other, but as the partner, the model, even the friend, then the West may have lost them for generations, not merely for an election cycle.

There is a temptation in Washington and Brussels to treat this eastward drift as a temporary marriage of convenience, born of sanctions and Russian fear. But that underestimates how much a new generation can internalise, and how economic dependence soon bleeds into military partnership and eventually a kind of spiritual alignment.

And it would be a strategic blunder of historic scale for Western Europe, in particular, to sleep through that transformation. For centuries, the Kremlin was a rival, yes, but a European rival. It played by broadly European rules, traded in European markets, shared a Christian cultural memory however faint at times. That left at least a possibility of dialogue. A Russia steered by Beijing’s priorities, bolstered by Chinese industries and Chinese political concepts, will be a different beast altogether.

That beast, if allowed to grow, will assist Beijing’s goals, not Europe’s. And it will carry with it not just Russian oil and gas, but Russian missiles, Russian resentment, and Russian manpower. Imagine a Eurasian bloc coordinated in its opposition to Western interests, stretching from the Pacific to the Baltic, with China in command and Russia as its willing lieutenant. Like the traditional US-UK “special relationship” on steroids.

That is a nightmare scenario for the West that its current policy all but invites.

America’s Worsening Solar Gap With China

China is emerging as the world’s first electrostate, the advanced superpower of this century, which could well be the Chinese century. Trump’s doddering old tattered America, blighted with toxic fracking pools and oil spills, crowned with opulence for the carbon-farting millionaires in their gated communities and with penury for harried workers in the minimum-wage strip malls selling poisonous micro-plastics as their wares, is staggering into the new century on arthritic knees, packing useless high-tech side-arms for a contest it has already lost.

Dangerous Submission

Merz’s vision is one of total mobilisation — a “whole-of-society” approach that seeks to prepare not just the armed forces, but the entire German economy and civil infrastructure for confrontation with Russia. Media, education, industrial policy and civil defence are all being aligned to support this new war footing. Dissent — whether political, journalistic, or academic — is increasingly stigmatised as subversive or even a threat to national security.

Ω Ω Ω

What we are witnessing is not a return of German nationalism, but its opposite. The policies now being implemented — from massive rearmament to the escalation of conflict with Russia — are not rooted in a cold pursuit of German national interests, but in their negation. They are the expression of a political class that has internalised the Atlantic ideology so thoroughly that it can no longer distinguish between national strategy and transatlantic loyalty.

Ω Ω Ω

Merz, while publicly critical of Trump, is in fact executing Trump’s vision: pressuring Germany to drastically increase defence spending, take over leadership in the Ukraine war and sever energy ties with Russia. And yet they are presented as expressions of German and European sovereignty. Contrary to Schröder’s courageous stance against the US invasion of Iraq 20 years ago, Merz has also offered a full-throated endorsement of Trump’s recent attack on Iran.

The problem today then, is not German ambition, but German submission. And the tragedy is that this submission is being dressed up as strategic autonomy — a grim parody of sovereignty in an age of ideological dependency. If German leaders once understood that peace with Russia was in Germany’s fundamental interest, today’s leaders act as if permanent conflict is a condition of responsible statecraft. That reversal is not only dangerous for Germany, but for Europe as a whole.

„Stopp dem Krieg gegen Iran!“ at the Bundeskanzleramt on a pleasant evening in June

There were more people than I could count on my fingers and toes!

A speaker verbosely informed us about why we were all there, which proved useful, as a certain faction of the audience persisted in chanting about Palestine however stopped when firmly instructed as to why we were there.

Before too long a squad of Polizei appeared to make sure this unruly crowd didn’t get out of hand.