When I was a kid my parents had the American Heritage photographic history of WW II on a bookshelf in our living room. I remember poring over the thick blue volume with my dad, asking questions. Where is Ploesti? Who are those people? What are they doing? Why? How could that happen?

When I was a kid my parents had the American Heritage photographic history of WW II on a bookshelf in our living room. I remember poring over the thick blue volume with my dad, asking questions. Where is Ploesti? Who are those people? What are they doing? Why? How could that happen?

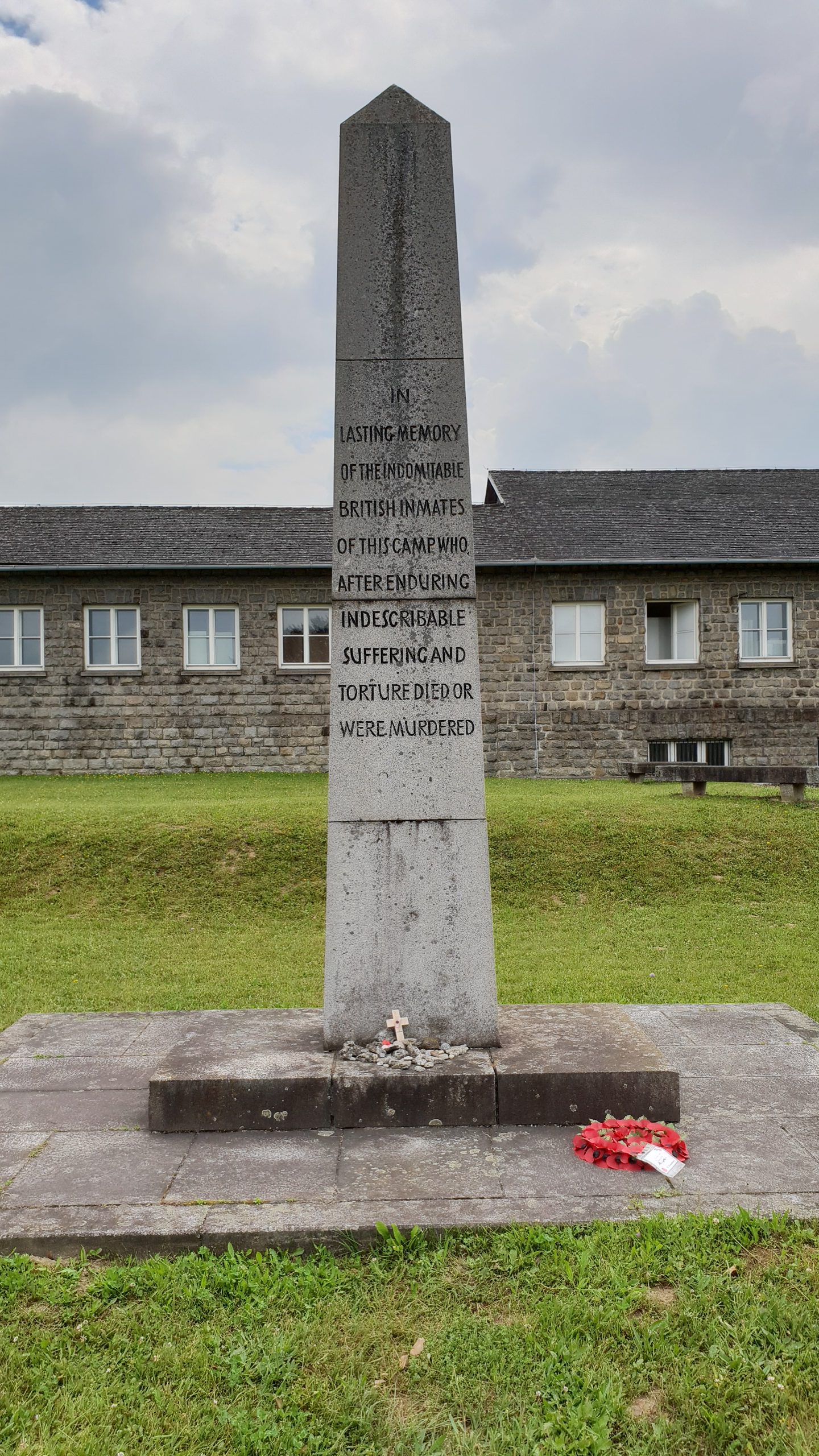

There was a photograph of the quarry steps at the Mauthausen concentration camp, with the caption stating that the men carrying large blocks of stone up the long staircase were American PoWs. Prisoners at the camp, the book said, were worked to death, trudging up the stairs again and again.

As a child the adult world is a mysterious place, full of wonders and horrors. There were any number of things I didn’t understand, but trusted that one day, when I grew up, I’d know. This generally proved the case, with geography, math, Vietnam. Some truths, however, remain elusive. The mass murder of the Third Reich continues to prompt American adults to ask „how could that happen? How could people do this? How could people let this happen?“

I visit KGB prisons, Nazi and Soviet concentration camps for a number of reasons. One meaningful role for me is that of witness to the experiences, the suffering, of those like me. My heritage is not Jewish but lapsed Catholicism. I am not especially drawn to the Jewish memorials at camps, but to those remembering political prisoners. The Nazi concentration camps were, after all, built first and foremost to imprison the politically suspect, long years before Kristallnacht. I see the cells which held members of the Red Front, the SPD, pacifists, dissidents of one sort or another, and I think, these were my brothers. In that time, in that place, I might very well have lain bruised on the cot in that cell. It could easily have been me strangling to death suspended from that beam. Alone in the dark icy water of this dungeon, I would have wanted someone to know I was here. Today, in the sunshine of a pleasant Austrian summer day I feel the responsibility to bear some kind of witness for those who are now silent.

I’m curious about these places. The Nazis, Stalin’s men, the Ustashi, are the fiends of American nightmares. The camps are a circle of hell only whispered about. I remember in elementary school on the way to the library I saw a strange symbol drawn on the sidewalk and curious asked my mother what it was. „That’s called a swastika,“ my mother said (what a strange word to a gradeschooler), and her face changed. „That’s a horrible thing.“ I maintain some of the childhood curiosity that just asks what was it? What happened? What was it like? How could that happen?

How could that happen? How could people do that? How could people let that happen? Into my 50s along with others I’ve continued to ask what seemed unanswerable questions. It occurred to me very recently that I finally have an understanding of how the Third Reich could come to be. I hear it in the naive statements of faith in an obviously bankrupt political system. I hear it in the expressions of fealty to the armed forces of an imperial power. I hear it in the voices of coworkers who speak of the safe mundane while privately they fear. I hear it in the location of corruption elsewhere, the finger-pointing at The Russians. I hear it in the despair of family, coworkers, friends, who see nothing to be done. I look at these quarry steps and I finally feel like I understand.